We attended the inaugural Murcutt Symposium in Sydney – a three-day celebration of architecture, place and legacy convened by the Glenn Murcutt Architecture Foundation. Held on 11-13 September 2025, the symposium brought together architects, students and designers for talks, house tours and conversations centred on Murcutt’s work and influence over more than five decades.

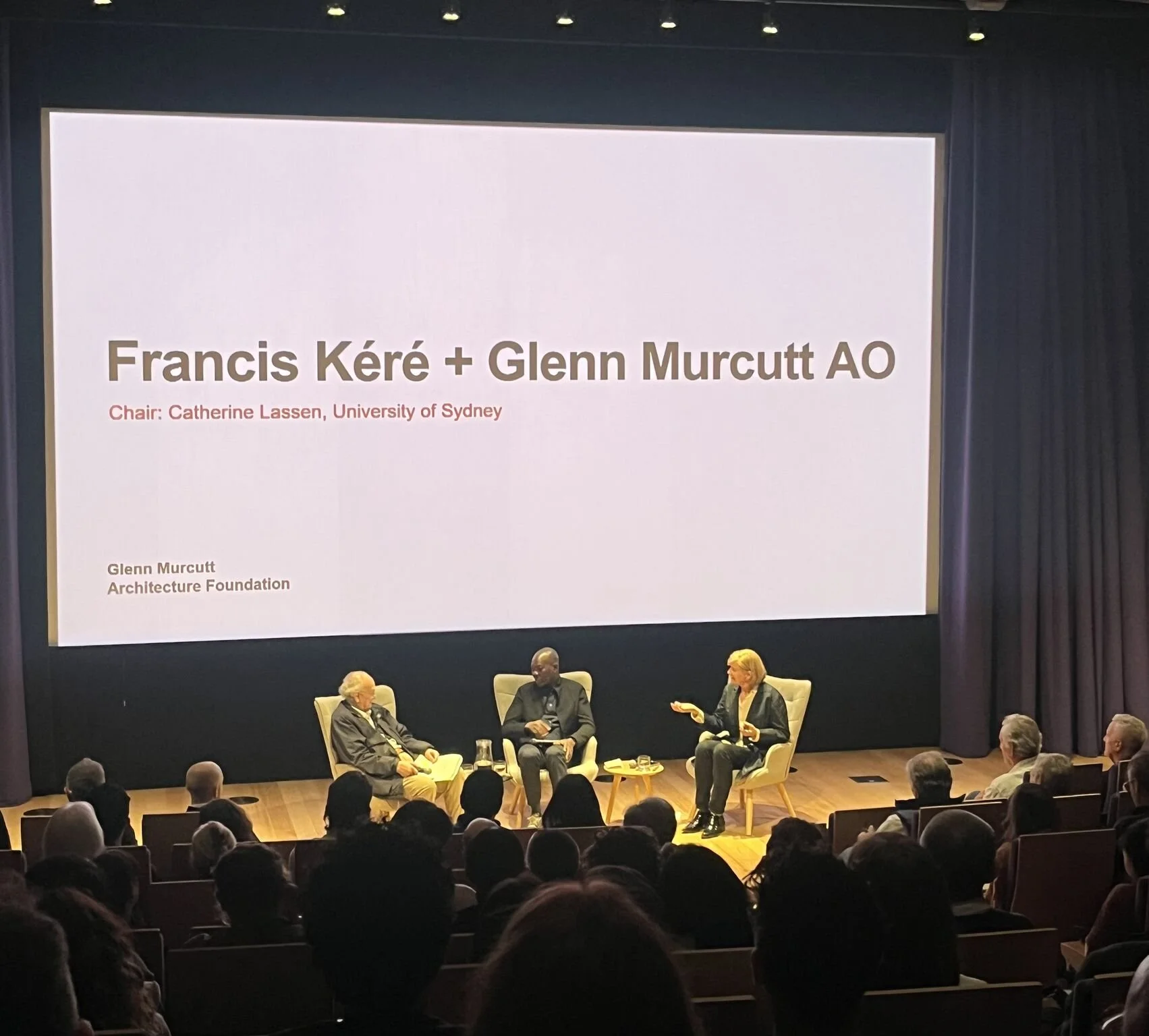

For us, one of the rare privileges of the weekend was hearing from two Pritzker Prize laureates in a single day: Diébédo Francis Kéré, the first African architect to receive the Pritzker Prize in 2022, and Glenn Murcutt, Australia’s only Pritzker laureate, recognised in 2002.

His key takeaway from the day was simple but powerful: both Kéré and Murcutt placed the role and relevance of community at the very centre of contemporary architecture.

Francis Kéré: ‘ordinary things, extraordinarily’

Born in Gando, a small village in Burkina Faso, and now based in Berlin, Francis Kéré has built an international practice around community-driven, low-tech, climate-responsive architecture.

At the symposium, Kéré reflected on his early training as a carpenter and on projects like Gando Primary School, where villagers literally built the school for their own children using improved earth and brick techniques developed together with his team.

He spoke about the power of doing “ordinary things extraordinarily” – not chasing spectacle for its own sake, but elevating everyday buildings through care, detail and shared ownership. In Gando and many of his later projects, the construction site doubles as a forum for knowledge transfer and community building, with local residents learning techniques that they can continue to use long after the architects leave.

For a practice like Reactivate, which spends much of its time thinking about how public spaces actually work for people, Kéré’s approach underscores the idea that process is as important as product: the way a project is conceived, communicated and constructed can be as transformative as the final form.

Glenn Murcutt: designing for a ‘complete community’

The symposium was also a chance to hear directly from Glenn Murcutt AO, whose influence on Australian architecture is hard to overstate. Murcutt’s body of work ranges from the Arthur and Yvonne Boyd Education Centre on the Shoalhaven River to the Cobar Sound Chapel and the Australian Islamic Centre in Melbourne – projects that are deeply attuned to climate, landscape and the people who use them.

We have had the opportunity to work with Murcutt and Candalepas Associates over the last few years on the Royal Far West Manly redevelopment, a project he describes as a career highlight. It was especially meaningful, then, to hear Murcutt say that this is the project he is most looking forward to seeing realised – his first building that will truly function as a complete community, bringing health, education and support services together on a single coastal site.

At 89, Murcutt is still actively designing. He joked that his father taught him never to be in a rush to succeed – a philosophy that feels evident in his careful, incremental body of work, and in the way he continues to mentor and influence younger practitioners.

Why this matters to us

What tied Kéré and Murcutt’s talks together was not style, geography or scale, but a shared conviction that architecture is fundamentally about people and communities.

Kéré’s work shows how participation, material honesty and local knowledge can produce buildings that feel truly owned by their users.

Murcutt’s work shows how patient, place-specific design can become a quiet backbone for community life, rather than a one-off object.

For Reactivate, the Murcutt Symposium was a reminder that our own focus on public life, community engagement and ground-plane experience sits within a much larger lineage of thinking about architecture as a civic act.

Spending a weekend listening to two Pritzker laureates talk less about iconic forms and more about community, stewardship and time was a valuable reset – and a timely prompt to keep asking how our projects can help build not just better buildings and streets, but stronger communities around them.